Inside Fima #2 – Life and sensitivity of Cesare Monti

INSIDE FIMA: news, ideas and insights to start exploring the world of the Italian Federation of Art Dealers and the gallery owners who are part of it.

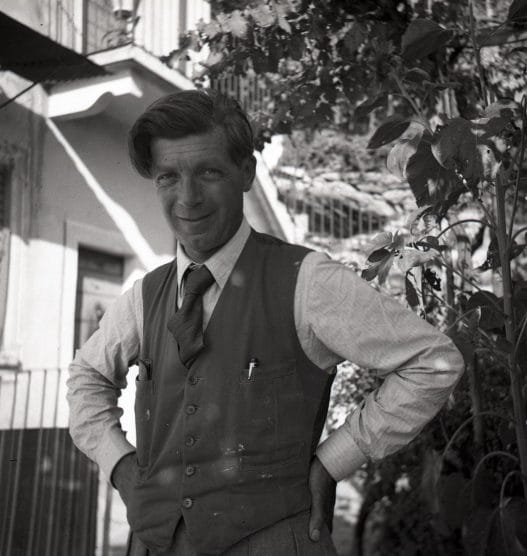

Cesare Monti to Corenno Plinio, 1944.

In 1906, at the age of thirteen, Cesare Monti was literally sent to Paris by his father, a barber in Brescia, in the hope that his young son would continue his work. The result will be different, given that upon his return in 1908, Monti will have the thought and desire of becoming a painter clear and fixed in his head.

In 1912, thanks to a scholarship from the Municipality of Brescia, he moved to Milan, where he began his activity as a painter. These were years in which Monti's painting moved towards a pointillist language, essentially linked to the work of Seurat.

In 1915 he opened the studio in via Bagutta at number 11, but the advent of the Great War, in which he took part, forced him to take a long break.

Evidence of this period are the popular skits filmed when he was in Dalmatia: these are paintings influenced by the Nabis painters, which Monti painted until around 1918.

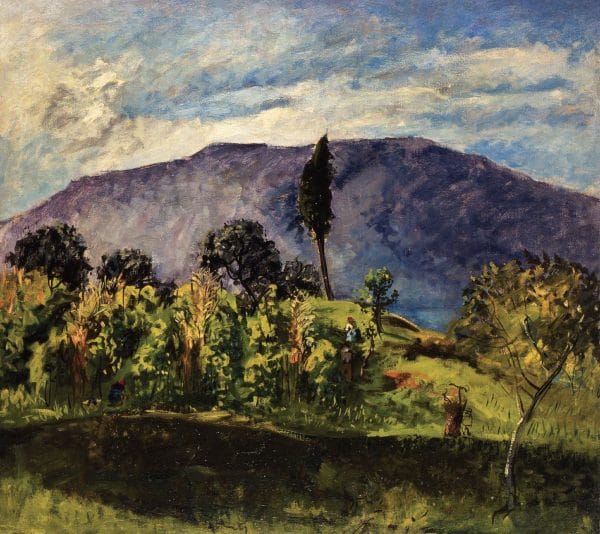

“Landscape in Colico”, 1931 – oil on canvas, 90×100 cm

After the Great War his painting abandons the candor that distinguished it and begins to evolve into a new language: the study of the ancients takes over, the figures and compositional systems bring us back to the first Italian Renaissance. Milan influenced him and his contacts with Margherita Sarfatti's future Novecento group became closer; Monti will never be particularly loved by the godmother of the twentieth century, probably due to his character considered too candid, yet he will carve out important spaces for himself both within the exhibitions of the "extended" group and with his presence at the Biennale, widely rewarded by the public and by critics.

And it was precisely in 20 that his pictorial adventure linked to the Novecento group began: he made his debut at the Venice Biennale, to which he would always be invited until 1950 (in 1940 with a personal room with 28 works), collecting fourteen participations; in 1930 he was awarded the Omero Soppelsa Prize for the best landscape at the Venice Biennale, no small prize for a self-taught man, especially given the excellent participations that year.

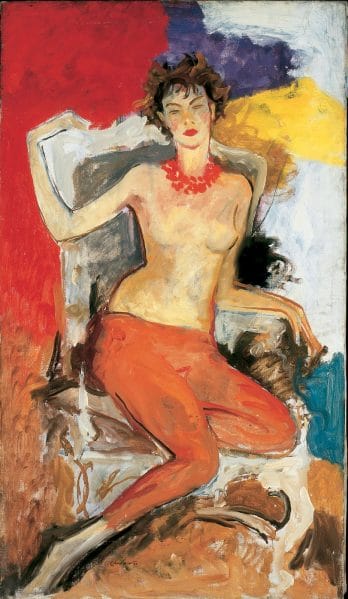

“Red necklace”, 1956 – oil on canvas, 130×75 cm

In 1926 he took part in all the exhibitions organized by the Novecento Italiano committee: I Mostra di Novecento Italiano, Milan; Italienische Maler, Kunsthaus di Zurich; Novecento italiano, Kunsthalle, Hamburg, June 1927; Exhibition of Italian Art in Holland, Amsterdam October 1927.

In 1924 he was also victorious at the Magnocavallo prize; in 1926 the Fornara prize; 1927 Guido Ricci Award; in 1932 the Omero Soppelsa Prize.

In 1928 he followed the portrait of Mrs. Boschi Di Stefani, today in the main sun of the homonymous museum house.

Although landscape was recognized as his great specialty, figures and portraits were requested of him by the most important Lombard families, thanks to his sensitivity and ability to capture the spirit of the portraits, fusing the freedom of the impressionist brushstroke with twentieth-century immobility.

In 1930 he was invited to exhibit at the Permanente together with Carrà, Marussig, De Grada and Tosi.

“Glass with roses”, 1926 – oil on canvas, 30×50 cm

In February 1929, upon invitation, he participated in the second exhibition of the Novecento Italiano at the Permanente where he exhibited two works; in March he was in Nice where the Exposition du Novecento Italiano opened at the Société des Beaux-arts. Painting, sculpture, decoration. In 1930 he exhibited in Buenos Aires at the Novecento Italiano exhibition and in 1931 he exhibited in Munich and Stockholm, in the Il Novecento Italiano exhibition; again in 1931 he was invited to the I Quadrennial in Rome, in 1930 he exhibited at the Pesaro Gallery with Bucci and Steffenini; again at Pesaro in 1932 with Frisia and Vellani Marchi (presented by Enrico Somarè); in 1934 again with Novecento in Stockholm, Oslo, Hamburg, Bern, Pittsburgh, Buenosa Aires; in 1938 again at Pesaro in the collective Quattro pittori lombardi; in 1939 he was invited to participate in the First Corrente exhibition, despite the stylistic and idealistic distances with the young rebellious painters, who however showed great respect for the coherence of his artistic path.

It is also right to remember the chair as Honorary Professor of Brera in 1924 and that of 1939 at the Academy of Fine Arts of Apuania Carrara.

The incessant need for updating shines through Monti's work.

“Young woman”, 1932 – oil on canvas, 72×50 cm

His pictorial evolution continues until the end, moving from the initial divisionism to the more rigid canons of the twentieth century to a freer painting executed without drawing, on the wave of impression, to arrive at a courageous and conscious confrontation with new trends, in a sort of figurative/informal style that makes the works of recent years of great interest.

Many wrote about him, but it is nice to quote Alfonso Gatto's memory from 1968:

”[…] During the last years of the war and of clandestinity, from '43 to '45, I was very close to Cesare Monti. In Corenno Plinio, where Lake Como becomes large and deserted, I too was displaced. There were Carrà, Barbaro, Colognese. Monti had his house and his studio on the edge of the small town, towards Dorio, and I went to visit him there every evening. He never showed me his paintings, I saw them myself, hanging on the walls, or I had to look for them myself with discretion and with annoying curiosity at the same time, holding them up to my gaze askance, almost subterfuge.[…] He was there in every work and in each operetta, a relaxation of rhythm and pictorial phrase, ever broader and more consonant with the accents that gave it timbre and joy: a hidden poetic feeling that still lives on and that a thoughtful anthology of Monti's works will have to re-propose.

That was the season in which I worked on the poems of "Love of Life". Monti, passing by bicycle towards Dervio, turned his head, whistling at me, knowing that I was there in front of the balcony spelling. He smiled quickly at me with his clear eye, as if to confirm that the whole secret still lay in "looking" and in finding accents of celebration even for the darkest days.

“To the fields (the family)”, 1921 – oil on canvas 50×60 cm

“In one leap the heart, awake, will have words…”, I read to him one day from those verses, and he, cloaked, hugged me from behind, also bundled up and ritualistic like a puppet of fog. Soon we would have freed ourselves of every dress and every uniform, we would have regained the sun and living life. He was certain of it: a quiet human faith, his. The long silent conversation with painting gave him secret help and patience and irony for every humiliating authority. With the most frank air, almost as if he didn't give himself credit for it, Monti then proved to be a very civilized man of culture.

Monti was a particular man of culture. He knew more than he showed: his books and the beautiful simplicity he managed to have with his young children gave an account of it: a memory, an example, unforgettable for me.

In that ironic man, attentive and distracted at the same time, there was hidden almost with modesty, an actor of subtle, witty and provocative intelligence, who nevertheless wanted to give little consideration to his dexterity and his intellectual implication, to stick to the simplicity and uninterrupted thread of the his “seeing”. His dedication to evidence was more tenacious in him, to a visibility offered and I would say, with an image that signifies goodness and beauty for him, to the balcony of living life. He wanted to be, and is, a natural world inhabited naturally by man. It is in this furrow, in this Lombard smell, that Cesare Monti leaves the mark of his pictorial poetry. We will continue to see in his canvases the luminous offering of his eyes”.